Lessons from Nairobi: Why we must not forget the material realities of AI

For Imogen Parker of the Ada Lovelace Institute, a Nairobi event on the global labour supply chains involved in AI and its environmental impacts re-anchored her mental image of the technology – and its fundamental relationship to people, materials and work. She explains why ‘bringing AI back down to earth’ is so important for policymakers

Last week, the UK saw a political reshuffle and a new secretary of state for science, innovation and technology, as well as emerging details of a new UK-US trade pact.

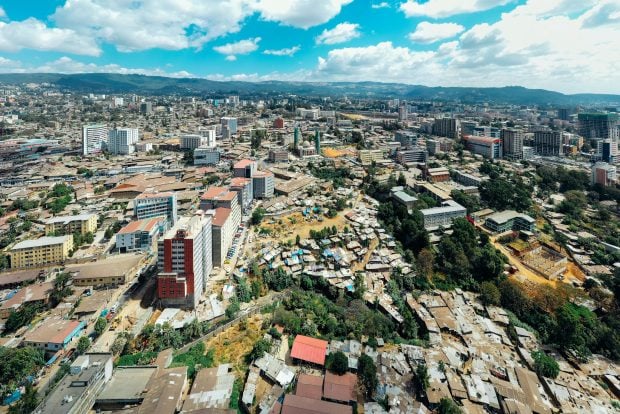

However, rather than carrying out the usual policy activities you might expect – drafting introduction letters, combing through previous speeches, commenting on emerging news – I was literally and figuratively miles away from the day-to-day of UK policy, spending a week in Nairobi.

I attended the Global Fund for a New Economy 2025 Global Convening on the Political Economy of AI and Digital Technologies. The event was framed around the reality of how AI and digital technologies are rapidly reshaping the world, while inextricably tied to a concentrated US technology sector.

The event brought together leading voices from around the globe, each bringing different perspectives and experiences onto the political and economic realities underlying AI and digital technologies, focusing on work, climate and digital public infrastructure. It sought to build a new cross-border understanding but also to explore tangible actions for supporting a new or alternative political economy for AI, one that works better for people, society and the planet.

The convening covered a lot of ground, but here’s one immediate takeaway.

Read more: Do we need a ‘What Works Centre’ for public sector AI?

AI as material

Debates about AI are often conducted in very abstract terms, ungrounded from the tangible concerns of communities, even more so than most policy areas.

It’s easy for policy discussions to slip into a mental model of AI as immaterial; something we can’t see or touch but with incredible power.

‘Unleashing AI’, ‘We asked AI’, ‘AI will improve efficiency’.

Once you pay attention, you notice that much of the policy discussion around AI makes the mistake of talking about AI as an actor in itself, rather than considering the many different actors, from around the world, involved in the development and deployment of AI.

Last week’s discussions in Nairobi on the global labour supply chains involved in AI and the local environmental impacts re-anchored my mental image of AI, bringing it back down to earth as fundamentally related to people, materials and work. In terms of its impacts on people and planet, AI is as physical as any other industry.

Our previous work at the Ada Lovelace Institute has highlighted the importance of thinking about AI as the product of an extended value chain — but the value of convenings such as this one is the opportunity to further extend and make concrete our understanding of how far the value chain sprawls, and the policy and political challenges at each stage.

Any possible conception of AI as immaterial was firmly dispelled as I sat with data labellers in Kenya trying to improve their working conditions. I heard about the challenges in supporting informal workers to resist requests to photograph their children to strengthen datasets. Speakers discussed the human toll of work in the digital economy, from the impacts on gig workers to the psychological harm affecting content moderators and the experiences of miners extracting the physical resources needed to power AI. This material reality of AI is often absent from policy debates in the UK as it gets lost across distant, complex and opaque supply chains.

Read more: Troubling or trusted: Citizens’ sentiment on big tech in public sector AI

From global to local

AI’s impacts on work, public and shared resources, and environmental pressures show up closer to home as well.

Our own research explores the conditions by which the use of technology within jobs can be empowering or controlling – freeing up people to act with greater autonomy, or lessening autonomy through datafication and surveillance. Plans for new data centres are triggering environmental concerns, in terms of increased demand for water and energy.

An overly myopic focus on the productivity and efficiency benefits of AI adoption in public services – even if delivered on paper – can obfuscate the impact on jobs and acknowledgement of where work happens, for example, in the way that the normalisation of self-service tills has shifted work from employees to unpaid customers.

Grounding AI in the material helps us approach what can feel like novel and intractable questions using more traditional frameworks. AI is an emerging technology, but global supply chains, working conditions and environmental impacts are not new policy concerns.

Read more: Why public legitimacy for AI in the public sector isn’t just a ‘nice to have’

Grounding AI leads to better policy

Grounding AI in the material helps puncture arguments that AI’s novelty requires policymakers to respond by providing special license or unique freedoms to facilitate progress.

Having a clear-eyed vision of AI as part of a complex supply chain of work, assets and resources should help us ‘normalise’ policy discussions around it.

To make good choices about how AI is used and regulated, we need to resist being dazzled by what’s possible on screen, but think about who is doing the work, and what resources lie behind the technology.

AI is new. But policy decisions to balance power, share profit, value work and ensure environmental stability are not. Grounding AI should help ensure public servants consider a fuller picture of impacts, and ensure that public interest AI meaningfully delivers for the public.

Read more: ‘Radical reimagining’: lessons for the use of AI in public services and policymaking