Economic ventilators: how to build a stimulus package

The governments of locked-down nations agree on the need for vast cash injections to keep their halted economies ticking over – but European states are taking a very different approach from the USA. Natalie Leal explains their contrasting strategies

Since COVID-19 first emerged in Wuhan, it’s taken just four months for it to bring many of the world’s biggest economies to a virtual standstill, causing what Bpifrance executive director Nicolas Dufourcq has called a “financial heart attack”. Across the West, where governments haven’t had to deal with a pandemic for a century, they initially reacted too slowly to control infections – then, when coronavirus had become established, imposed drastic controls on people’s movements in a bid to slow infection rates and prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed.

With many company staff unable to do their jobs, the risk is of huge lay-offs – with organisations both unwilling to pay inactive workforces, and shedding staff in anticipation of the inevitable recession to come. And swathes of the freelance workforce can’t earn a living, threatening them with impoverishment and bankruptcy. In an attempt to put their economies on life support until movement restrictions can be lifted, many governments have borrowed to fund vast stimulus packages – dwarfing the money injected to address the financial crisis a decade ago.

But how should those funds be spent? Countries have taken quite different approaches: here we profile the British, French and American rescue packages, finding a stark difference between the Europeans’ supply-side measures and the US’s focus on propping up demand.

France

As shops were shuttered and French citizens ordered to stay indoors, President Macron reassured the nation that “no business, whatever its size, will face risk of bankruptcy” – rolling out one of the first big stimulus schemes.

To protect French business and livelihoods, the government has rolled out a number of business support measures, totaling about €345bn (or US$377bn, equivalent to 15% of GDP) in grants and loans. To enable companies to keep staff on their books, the government has introduced a ‘Partial Unemployment Scheme’ whereby firms can ‘furlough’ inactive employees while continuing to pay them – reclaiming up to 70% of a furloughed worker’s salary from the government. Employees on minimum wage will have 100% of their salaries refunded.

Other measures include deferred payments for utilities and rent for affected companies, and accelerated VAT refunds. Micro-businesses and freelancers who go bust or experience a loss of turnover of at least 50% will be given direct payments of up to €1500 (US$1640). Additional aid of €2000 (US$2190) will be available for “companies experiencing the most difficulties, on a case-by-case basis, the government says.

Adjustments were made after concerns were raised about start-ups, many of whom are not yet in profit and so wouldn’t have qualified for government help. Keen to protect this sector, the government has since added €4bn (US$4.4bn) to fund a mixture of government-backed loans and bridge funding for start-ups hit by fundraising issues during the pandemic.

Dr Alexis Crow, lead of PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Geopolitical Investment Practice, says the French government’s support for French start-ups “is both laudable and crucial.”

“In part due to organic growth, and partly due to a geopolitical ‘offset’ from Brexit, France holds pole position of being the start-up capital of Europe,” she says. “This must continue.”

United Kingdom

The UK’s fiscal stimulus package promises £350bn (US$430bn) for businesses, totaling over 15% of GDP. Small and medium sized businesses can access cheap loans of up to £5m (US$6.2m) from the Covid Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF), and larger firms can raise capital quickly and easily from the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS) agreed with the Bank of England. Business rates will also be suspended for shops and restaurants. Unlike the French scheme, the UK’s offer does not include direct financial support for start-ups that have yet to turn a profit, raising the prospect that they may be particularly hard-hit.

Meanwhile the ‘Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme’ will provide grants of up to 80% of the wages of employees unable to work, to a maximum of £2500 (US$3100) per month for an initial period of three months. The scheme is expected to be up and running within a month, and meanwhile firms can borrow from the government to fund the salaries of furloughed staff. But self-employed workers were initially left unprotected, told that the government would “strengthen the safety net for those who work for themselves” by increasing unemployment benefits, extending statutory sick pay and deferring tax payments.

These measures, which left many freelancers facing a collapse in their monthly income to about £400 (US$500), were widely criticised for threatening the livelihoods of self-employed workers and undermining adherence to the government’s lockdown measures: many people felt they simply had to go out and earn a living. Under pressure, chancellor Rishi Sunak has since added a further £60bn (US$74bn) to provide self-employed workers with grants worth 80% of their previous profits for the next three months; the government intends to assess payments by calculating the average of three recent tax returns. The ‘Self Employed Income Support Scheme’, with payments starting from June, will provide grants to all self-employed workers who’ve submitted a 2018-19 tax return, made less than £50,000 profit in that year, and are now experiencing a dip in earnings.

Some of these self-employed people will end up receiving grants greater than their lost earnings. But Christian Odendahl, chief economist at the Centre for European Reform, says governments need to accept “that some money will be paid out without justification to people who don’t need it.” The need to roll services out at speed makes it impossible to recognise and address all the complexities that will lead to inequitable outcomes; and the alternative to speed, he argues, is widespread loss of jobs and businesses.

Equally, some groups of workers remain largely unprotected. The directors of one-man companies cannot apply for the self-employed scheme, for example, and nor can the self-employed who began trading too late to submit a 2018-19 tax return.

Inequities and debts

The corona response has two goals, says Odendahl: to “hibernate the economy without causing unemployment and insolvency”, and then to “create a decent and proper recovery once it is safe to do so.” This “requires massive fiscal spending and loans to businesses: for example, subsidies to keep workers on the payroll, and liquidity loans on very low interest rates.” Within that macro picture, though, there will be many unjust outcomes at the micro level: as he points out, it’s “tricky to get into all the cracks of a highly diverse economy.”

But questions remain about the amount of debt companies and directors are being asked to take on. The UK and French government’s attempts to place the economy in suspended animation – supporting firms and workers to pick up where they left off as lockdowns are eased – risk burdening firms with huge new debts as a major new recession looms. Easy access to loans and grant-funded salaries will not prevent many firms from laying off staff if they fear that they’ll end up making people redundant anyway in the following months.

For Odendahl, the solution lies in governments giving businesses confidence that they’ll only repay loans if market confidence returns. “Governments should announce that part of these loans will be forgiven if the economy as a whole fails to make a strong recovery after the epidemic is contained,” he recently wrote. “Companies should not be responsible for governments’ failure to overcome the virus and create the conditions for recovery.”

United States

Across the Atlantic, the US is taking a very different approach. Adopting the ‘helicopter money’ strategy, the government is showering the public with cash – ensuring that people can pay bills and keep spending through the lockdown, whether or not they can earn.

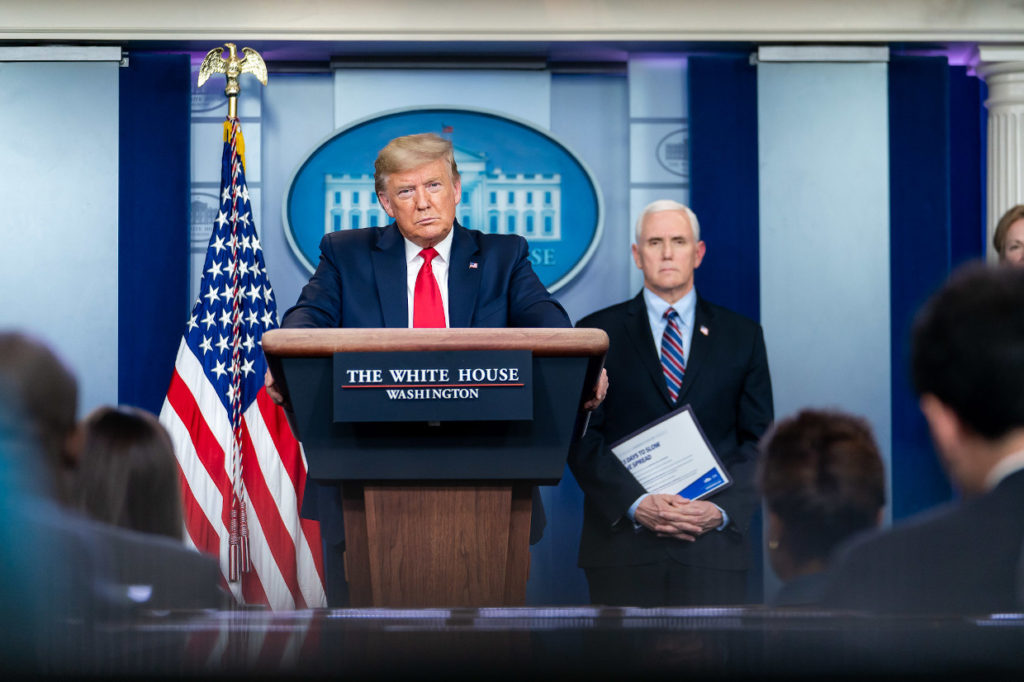

Last week, Trump signed an eye-watering $2.2 trillion fiscal stimulus package, equating to roughly 9% of GDP – and double the size of Obama’s intervention after the financial crash in 2008.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) promises a cash handout of up to $1200 for nearly every American. And meanwhile the administration has beefed up unemployment benefits: Americans who find themselves out of work will get an additional $600 every week on top of state benefits (which range from an average $200 to $550 a week, depending on the state). This programme has been expanded to include gig workers and the self-employed for up to four months. Student loan payments have also been suspended until September.

$360bn has been set aside for loans and grants to assist small businesses, while large firms such as airlines – which have been hit hard by the pandemic – will have access to a $500bn bailout fund consisting of loans and investments.

The markets initially responded well to Trump’s stimulus package, but the focus on propping up household incomes rather than funding company wage bills has left businesses shedding vast numbers of staff. An extra 3 million unemployment claims have been registered in just one week, with New York City – one of the areas most affected by coronavirus – experiencing a 1000% increase in claims. The US appears to banking on its helicopter money to keep people spending in the short term, in the belief that lost jobs will quickly be recreated as movement restrictions ease.

Which way forward?

Economics professor Jonathan Portes of King’s College London says the UK and French approach “appears better targeted” than the US strategy. “In the short term, the impact of the restrictive measures taken to contain the virus is a supply shock, not a demand shock,” he explains: while consumers may currently find it hard to buy some goods, the first impact is felt mainly by businesses unable to operate normally. The European approach hopes to “prevent long-term damage to the supply side of the economy, by ensuring that business failures and job losses are kept to a minimum,” he says, “although there is a large risk that the measures won’t come online quickly enough.”

Odendahl also believes the European packages will better protect businesses and workers in the long term. “The US approach – not just now, in general – is more geared towards destruction of unproductive businesses and letting new businesses emerge. [This] creates a lot of dynamism in the economy, but can also destruct successful companies in deep crises, such as the current one,” he says.

“If such companies are destroyed, lots of capital and knowledge and worker-firm relationships are destroyed with it that you would like to keep. So the European approach, to keep businesses intact as is, tries to save viable businesses and the physical, human and other capital that has been created. It may lead to unproductive firms surviving – but I am not sure that is a big problem at the moment, considering the severity of the crisis.”

In both Europe and the USA, says Crow, “what is absolutely critical are the ways in which these policies – designed to shore up the real economy – are communicated to voting publics.” After the financial crisis, she points out, the public grew to believe that they’d bailed out the finance sector only to experience years of austerity and wage stagnation – even as quantitative easing and economic changes allowed the rich to keep on improving their lifestyles. “Amidst deepening income inequality in advanced economies, many voters still hold resentment for the bank bailouts of the Great Financial Crisis,” she says. “The legislation implemented thereafter – which prevented another wide-scale financial crisis – seemingly did not trickle through to their incomes or purchasing power.”

As leaders fashion their responses to this latest global crisis, she argues, “it is mission-critical for policy officials – elected and, in the form of central banks, unelected – to clearly communicate how they are saving blue collar jobs.”

In many ways, the current leaders of the USA, France and the UK owe their positions to public anger at how things have played out since the financial crisis. If they don’t learn the lessons of their predecessors’ defeats, they may be doomed to repeat them.

Reminds me of how the UK dealt with the problem of banks going out of business (not the reasons behind it – but that’s another issue). By this I mean providing money to banks directly rather than via paying down the debts of the people of the UK. Socialising the cost of business failure without socialising the benefit is not “better” targeted, just targeted to help the already wealthy while ensuring no real benefit to the ordinary tax payer, who at best ends up slightly worse off.