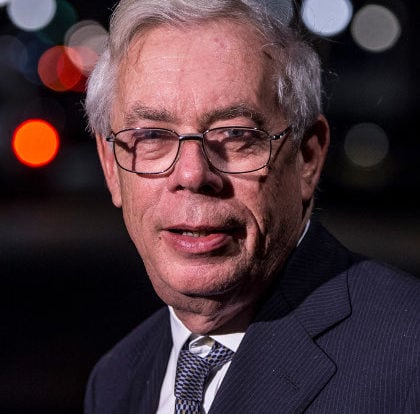

John Kay, visiting professor of economics, LSE: Interview

Economist and public policy expert John Kay tells Winnie Agbonlahor how the Thatcher era brought fundamental change to Britain’s civil service, and why he helped set up one of the UK’s most influential think-tanks

Britain’s civil service prides itself on being impartial, loyal to whichever political party forms the government but ready to ‘speak truth to power’ in the interests of good policymaking, ethics and the proper use of taxpayers’ money. But John Kay – one of Britain’s leading economists and an observer of the civil service for more than 40 years – believes that, after three decades of creeping politicisation, civil servants today are less willing to tell ministers uncomfortable truths.

His theory is reflected in concerns recently voiced by Sir David Normington, who retired as civil service commissioner last month. He said that, in his experience, ministers try to interfere with senior appointments as frequently as once a month, and warned that the principles of having an objective and impartial civil service are now under threat as politicians chip away at the principle of appointment on merit.

Under reforms mooted in a review conducted by Sir Gerry Grimstone, a senior business figure and civil service non-executive director, ministers would have more power over the composition of selection panels, as well as the ability to override their recommendations or to appoint a candidate without a selection process.

The current system, under which the prime minister chooses permanent secretaries from a shortlist of candidates selected by the Civil Service Commission, is itself the result of reforms introduced in December 2014. Previously, the commission selected a single candidate for approval or rejection by the PM. Nonetheless, today’s appointments system is largely based on recommendations made in 1995 by the Committee on Standards in Public Life – appointed under the chairmanship of Lord Nolan to address widespread concerns that appointments were the result of political bias. His report, which set out seven principles of public life (selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness, honesty and leadership), recommended important “checks and balances” on ministers’ “considerable powers of patronage”.

In his official response to Grimstone’s recommendations, Normington called the proposals a “step in the wrong direction” and said that their cumulative effect “would be largely to remove the checks and balances recommended by Lord Nolan 20 years ago.”

However, Kay – who is a visiting professor of economics at the London School of Economics, an author and a columnist for the Financial Times newspaper – argues that Nolan’s report failed to prevent a steady politicisation of the civil service which dates back to Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. Thatcher, who was prime minister between May 1979 and November 1990, became one of the most divisive figures in British politics as she privatised large chunks of industry, attacked the power of trade unions and liberalised markets.

“I think part of it was having a more ideological government, so the phrase: ‘Is that person one of us?’ – meaning someone who shared broadly their world view, which was not a lot of people in the civil service at that time – became characteristic of the Thatcher years,” Kay says. Given the civil service’s long-established and resilient culture, he adds that it’s “understandable that Thatcher, coming in with a rather strong ideological stance, would have a justified feeling that there was a good deal of resistance among people to the sort of directions she wanted to move things in.”

It’s not that the civil service refused to implement the government’s policies, he adds, but that it did so without the passion desired by ministers. “It’s one thing to say: ‘We will do things that the government in power wants done, whatever they may be.’ It’s another to say: ‘We will be enthusiastic about whatever it is that ministers happen to want at the moment.’ And it’s very difficult for a neutral but honest person to shift from being gung-ho about one thing to being gung-ho about the opposite.”

Yet Thatcher’s ministers sought out civil servants eager to push forward their agenda, and soon those seen as “one of us” began rising fast through the ranks. This, he explains, was one significant factor leading to a more politicised civil service. The other, he believes, was the expansion of special advisers (spads). Today, spads are seen as “apprentice politicians”, he adds, but back then their arrival was a result “of the political mistrust of the civil service – the feeling that [civil servants] couldn’t be relied on to deliver what was wanted.” In this environment, he believes, “if you didn’t become more politicised as a civil servant, you were going to be side-lined” – and in his view that trend has never been reversed.

Despite the work of the Civil Service Commission in guarding the principle of appointment on merit, Kay argues that ministers “create the culture in which promotion takes place.” He adds that the core idea of the civil servant being “helpful” has changed meaning over the years: “What you mean by ‘helpful’ is subjective and depends on the environment. It might be telling truth to power, it might be being right, or it might be telling people what they want to hear. And an awful lot of people today want to be told what they want to hear.”

Meanwhile, Kay argues, there has been a gradual decline of the quality of senior civil servants. When he started teaching at Oxford University in the 1970s, the City – London’s financial capital – was seen as a career for “people who weren’t that bright but had good social connections.” But by the ‘80s, he adds, this had changed dramatically and a “high proportion of your best students were looking for jobs in the finance sector.” Not only did the City catch up in esteem; it also offers much, much bigger salaries than the civil service. “You would always accept less [money] in the public sector, but there’s a difference between a gap of 2:1 and one of 10:1.” To this day, departments see the growing pay gap between the public and private sectors as one of the biggest problems they face when attracting talent.

Fewer “high grade” people and an increasingly politicised climate have led to policy documents containing less technical know-how and more political fluff these days than previously, Kay says. In government papers from the 1970s, “even if you had political rhetoric at the front, when you looked a few pages in you actually had substantive analysis,” he argues, alleging that this isn’t true for documents drafted by today’s civil servants.

Casting his mind back to the ‘70s, Kay says he remembers often wondering: “Who knows what these people [senior civil servants] really think?” But today, he says, “you do know what they think.” Do senior officials not try to hide their political views anymore? No, the change is more nuanced, he explains: “I don’t think that the older generation were trying to hide it; I think it was a frame of mind. They probably had gone through their career not having political-type opinions, and I don’t quite see top civil servants of that frame [of mind] any more.”

In part as a reaction to this perceived change in the British civil service, in the 1980s Kay got involved with think tank the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). The IFS focuses on economics and public sector finances, and Kay says that its staff have always had to live and breathe an apolitical mantra of “being more concerned with the quality of public decision-making than its content.”

This concept was, and still is, unique for a think-tank, Kay says; he argues that he hasn’t seen a model like it anywhere in the world. “There are more, as it were, academically-oriented think tanks, which are really just branding academic research with a bit of a policy flavour,” he says. “I can’t point to a body like IFS in the United States; and if you can’t do it there, you can’t really find it anywhere, because that scene is thick with think tanks.”

The origins of the IFS go back to 1969, when four financial services professionals – bound together by a collective disgruntlement at the introduction of corporation tax by then-chancellor James Callaghan – decided to form an independent research society to study the economic impact of existing taxes and proposed changes in the fiscal system. With no established track record, the organisation was slow to attract attention at first; but today, the IFS is seen as the ultimate authority in Britain’s economic debate. Every time the government releases its Budget or other long-term strategic spending documents, the IFS’s findings on whether the chancellor’s political rhetoric matches reality are taken as gospel.

Kay, who first got involved with the IFS in the mid-’70s and took over as its director in 1979, sees his work on the organisation as his biggest career achievement so far. “One thing that helped a lot then was there was rather more willingness on the part of large corporates to support this kind of activity than there is today,” says Kay, who helped grow the IFS’s public profile during his tenure. Initially relying on donations from “a list of well-known large British companies, which gave a core funding that enabled the thing to have premises and get going,” the IFS nowadays draws much of its income from the Economic and Social Research Council – a UK government funding agency.

Could something like the IFS be established elsewhere in the world today? Other countries would certainly benefit from a comparable institution, Kay says. His advice: “Find money to make it happen – one or two rich donors who like the idea, to get the thing off the ground”; get journalists interested; and recruit a core group of people who share the vision of examining the process rather than the content of public decision-making.

In Kay’s view, though, it’s ever harder to find these apolitical figures. With the civil service so politicised over the last 30 years, he certainly sees that as a less fruitful recruiting ground. The media is highly politicised, leaving academia and accountancy as the obvious places to look. So thank goodness for the IFS, which grows its own impartial analysts; but if someone was trying to set it up today, Kay believes that they’d struggle to find people with the ability to focus on assessing the quality of decision-making rather than applying their own political lens to the decisions themselves. “It’s not impossible,” he says. “But it’s not easy.”

For up to date government news and international best practice follow us on Twitter @globegov

See also:

Leading economist calls on governments to stop shying away from large deficits

Sir Nicholas Macpherson, Permanent Secretary, HM Treasury, UK: Exclusive Interview

Robert Barrington, executive director of Transparency International UK: exclusive interview

Anti-corruption campaigner: “establishment corruption” threatens UK’s image overseas

Looking after number one: prioritisation in government

Tom Scholar appointed new permanent secretary of UK Treasury

Interview: John Manzoni, chief executive, UK Civil Service

Colin MacDonald, CIO for the government of New Zealand: Exclusive Interview