Leadership ranked as the most critical factor for government innovation

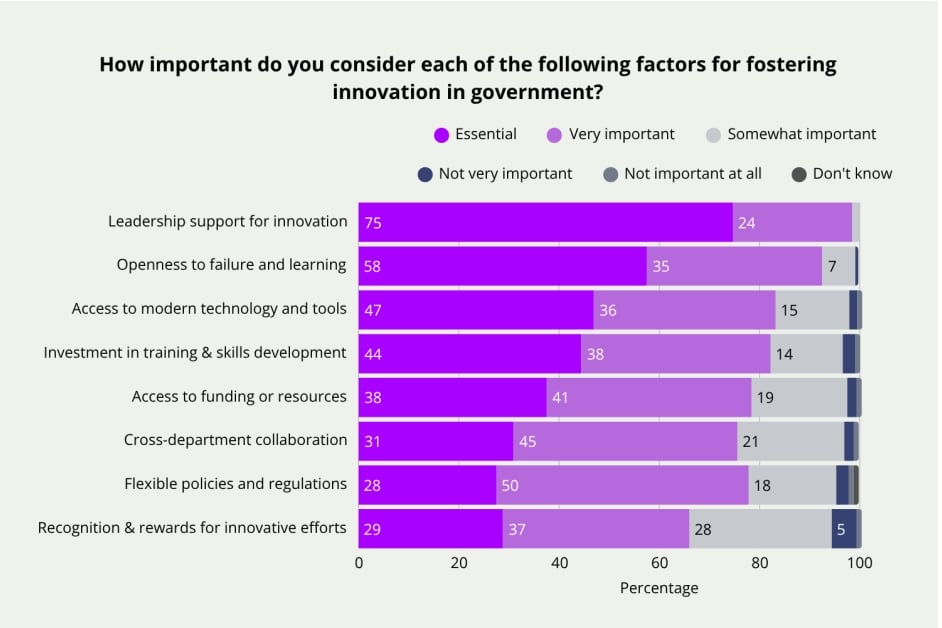

Leadership support stands out as the most critical factor for fostering innovation in government, with 75% of civil servants surveyed by Global Government Forum (GGF) rating it as essential.

The findings are from GGF research based on presentations and discussions at Global Government Forum’s Innovation 2025 conference held in London in March, as well as a survey of over 300 UK delegates – drawn from more than 3,500 event registrants.

Factors following closely behind leadership are a culture that embraces failure and learning, and access to modern technology and tools – both of which are also widely seen as critical enablers of innovation.

Training and skills development, along with access to funding, are recognised as important, though slightly less essential.

Interestingly, while elements like flexible policies, cross-department collaboration, and recognition for innovation are still valued, they are more often seen as supporting conditions rather than core drivers.

Creating an innovation culture

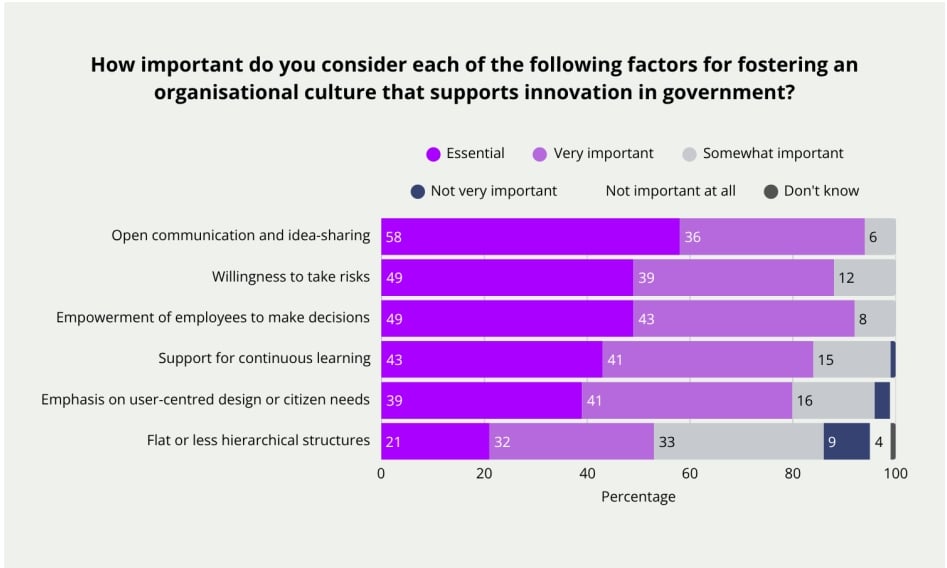

On fostering an innovative culture specifically, respondents ranked open communication and idea sharing as the top factor for success, with 94% saying it’s essential or very important.

Respondents made practical suggestions such as having “a forum for sharing innovative ideas” and more “cross-government and team information-sharing and knowledge-building”.

Close behind are willingness to take risks and empowerment of employees to make decisions, with almost half seeing these as essential.

One respondent said it was “the actual willingness to take risks that is letting us down”. They said that while leaders encouraged innovation, they’d had many ideas refused due to lack of time. It can “feel like lip service”, they commented.

Some believe that the opportunity to be innovative should be more inclusive, with one noting “The lower down the grades you go, the less scope roles offer for innovation, risk-taking and failure” and another saying that a culture should be fostered “where innovation is standard across all teams, not just digital”.

Support for continuous learning and emphasis on user-centred design or citizen needs are considered important as well, though slightly fewer view them as essential compared to the top three.

On learning, one participant called for “compulsory training for senior management on how to foster and encourage innovation” and another for “far more training, not just surface training on possibilities but actual practical training”.

Notably, flat or less hierarchical organisational structures receive the least emphasis, with relatively few respondents seeing them as essential – though many still consider them important to some degree.

The need to address bureaucracy as a barrier emerged as a strong theme in respondent comments, with one stating: “I often find innovation blocked by the cost to change a system even slightly.”

Another respondent raised the concept of specifically recruiting innovators. Today, they said, government “hires people with other skillsets and then asks them (sometimes) to innovate. Government needs to hire innovators specifically to perform the role of innovating. These may be people who might not necessarily make successful civil servants in the current culture. We need more ‘changers’ and fewer ‘status quo-ers’. Government needs to completely change what a civil servant is, how they work, what they do.”

Leading innovation

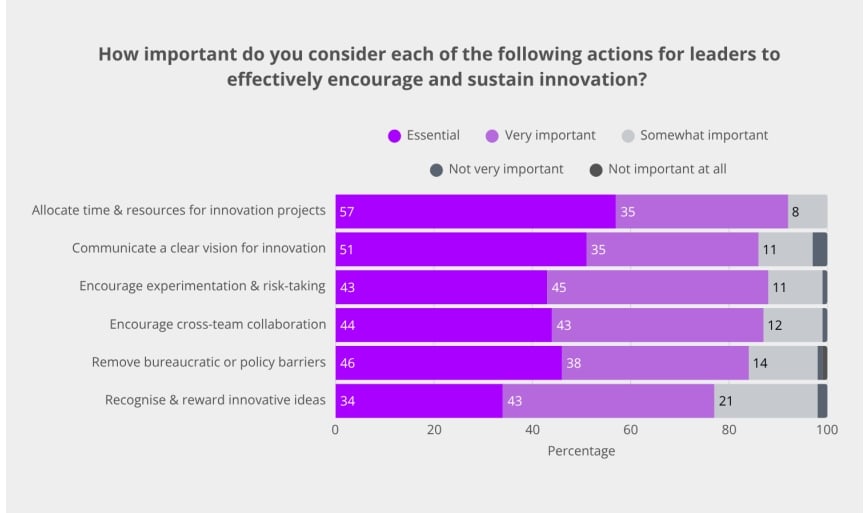

With leadership being such an important factor, we asked survey participants about the most important actions from leaders to effectively encourage and sustain innovation.

At the top of the list is allocating time and resources for innovation projects, which almost 60% view as essential.

Several participants stressed the need for dedicated time and space to focus on innovation and “allowing people the time to innovate and try new things”.

Close behind was communicating a clear vision for innovation, also seen as a critical action by most respondents, though some highlighted the need to retain openness. “I think having a vision tends to lock people into that vision strictly. Having a loose idea of the direction you want to move in can help guide but leave you open to changes within the change that end up being improvements,” one said.

Encouraging experimentation and risk-taking and encouraging cross-team collaboration rank next, with over four in ten viewing them as very important but slightly fewer considering them essential compared to the first two actions.

One respondent urged leaders to “empower staff and make sure you don’t judge too quickly when things go wrong”. Removing bureaucratic or policy barriers is another highly regarded action, with close to half viewing it as essential for innovation.

Lower down the list is recognising and rewarding innovative ideas but a third still see it as an essential action to drive innovation. One respondent called for leaders to “pay rewards and promotion for innovation that is taken up”.

Another respondent said that to make innovation “the essence of what the civil service is” rather than an “occasional” activity, leaders should encourage teams and colleagues to “compete to be ever more innovative, creating change on top of change, extending the scope of what’s possible”.

Another encouraged leaders to “prioritise how they engage with innovation”. “They should think about how they hear pitches and what they do with the pitches they’ve had,” they said. “If you’ve not had any, why not? What can you do to make yourselves more accessible?”

“New ideas are out there,” they stressed. “People have them all the time. It’s a question of making sure they get heard and helping them be actioned.”

Cultivating the right culture

During a panel session on how leaders can create an innovative culture in government, Emily Hobbs, director for capability, learning and talent at the UK Department for Work and Pensions, reiterated a strong theme that “a culture of psychological safety absolutely underpins a culture of innovation and for me, you can’t easily have one without the other”.

She said this extends beyond a culture where it’s safe to speak up and challenge to one where people feel safe to make mistakes, share openly, take risks and propose new ideas without fear of negative consequences, even when things don’t go as planned.

To make this a reality, Hobbs said that leaders play a critical role through four key actions. First, they must openly express their commitment to psychological safety and acknowledge that while it may not always be perfect, it’s a clear ambition. They must be mindful of their own behaviour, ensuring they model positivity and avoid reacting with frustration. Further, they should create simple and accessible ways for team members to provide feedback, helping leaders stay informed about the culture they’re shaping. Finally, courageous leadership is essential, she said: “Your teams need to know that you support them and that you have their backs.”

‘Benefits before challenges’

Gareth Bristo, associate director at the UK Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS), explained how the DBS has tried to embed this approach. Recognising that frontline employees often have valuable insights but may hesitate to speak up, DBS created a dedicated “innovation lab” – a safe space for staff to explore and develop ideas without fear of criticism or rejection. The organisation trained a core group of over 200 staff members to participate, encouraging inclusive and constructive engagement. A key principle of this lab is ‘benefits before challenges’, which shifts the focus from immediate obstacles to the potential value of an idea. Phrases like “Yes, and how can we make this a reality?” replace dismissive responses.

He said this approach not only surfaces a list of ideas that’s potentially feasible but also “you’ve got a group of people that feel safe to promote that now, because they understand how that’s going to positively impact the organisation, and then we can start to look at delivery…”

One Big Thing: Innovation

Sapana Agrawal, director for civil service strategy in the UK Cabinet Office, said that a key aspect of fostering innovation in government is aligning ministers, civil servants and leadership on innovation and risk-taking.

She highlighted recent speeches by Cabinet Office minister Pat McFadden and the prime minister about innovation and the importance of a test and learn culture. She called it “a real call to arms and permission for civil servants to innovate, to be creative”, while stressing the need for a shared language around risk and opportunity when pursuing new ideas.

As an example of support from leadership for civil servants to pursue new ideas, Agrawal highlighted initiatives such as the Civil Service Data Challenge – which Global Government Forum runs with the UK Cabinet Office, Office for National Statistics and NTT Data – and the One Big Thing initiative, which this year focused on innovation.

One Big Thing is an annual initiative for all civil servants to take action around a cross-government change priority.

“We asked the entire civil service to do innovation training, have structured conversations in their team, get leaders really comfortable leading these types of conversations and then experimenting and evaluating their efforts. And we got around 150,000 people involved,” she said.

Say no to the status quo

Jonathan Rushton, deputy director in the UK Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, said that an innovation mindset is crucial for fostering a broader innovation culture, especially in government where problem-solving is central.

“For me, a major part of it [innovation] is saying no to the status quo if we can see a better way of doing something and an opportunity and the benefits there,” he said.

Like others, he also emphasised the “test and learn” approach to encourage starting small, evaluating if ideas work, and scaling them if successful or learning from them if they don’t.

He pointed to government examples such as the Government Communications Service applying a percentage of its budget to more innovative approaches to communications and testing the impact; and central government working with local governments and others on using the test and learn approach to tackle specific challenges.

He said: “For me it’s the idea that might fail, but it’s not the person that had the idea that’s failed. I think that’s really central to how we think about this and how we can drive that experimental culture.”

Download the report for the full survey results and a summary of examples showcased throughout the event.