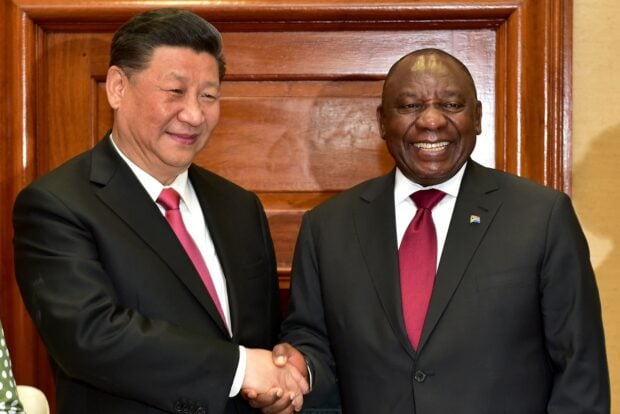

A tale of two countries: why has state capture seen China boom and South Africa bust?

Government structures in South Africa struggle under what observers call state capture. Ivor Chipkin, the director of the Government and Public Policy think tank, based in Johannesburg, sets out what this means, and why other countries in a similar situations seem to have thrived

After the democratic transition in South Africa in 1994, the ruling African National Congress (ANC) inherited both a highly fragmented government administration and a politicised public service from the apartheid regime. Instead of taking measures to professionalise the post-apartheid civil service the ANC chose rather to further politicise it. Distrustful of the preparedness of apartheid-era officials to implement ANC policies, and unable to fire them because of ‘sunset clauses’ in the negotiated settlement, successive ANC governments chose to bring their own people into government as a check on incumbents.

The influence of the New Public Management in the original design of the post-apartheid civil service – and then its specific elaboration after 2000 – created a cohort of “senior managers” in government departments with both discretion and institutional power, including over public procurement. Whereas elsewhere in the world, such arrangements seemed to promise a more entrepreneurial culture in government, in South Africa the senior management service became the privileged location where politicians were deployed.

The results of such measures were uneven across the government. In those departments and agencies where ministers or the ANC deployed suitable candidates, they performed adequately and sometimes excellently. The National Treasury is a case in point. The senior leadership was made up of people with ties to the African National Congress, though they were very often also outstanding professionals. Something similar happened in the newly-created tax agency, the South African Revenue Service. Elsewhere in government, the politicisation of government administrations did not turn out as well. The depth of talent in ANC networks was simply not wide or deep enough to properly restaff the state.

Predictably, these organisations have struggled to perform their most basic functions, as roads deteriorated, public infrastructure collapsed, and water purification works came to a halt. Combined with the crisis in Eskom, the state electricity company, many towns and cities have become dark and dilapidated spaces. The wide discretion of presidents and senior politicians in the appointment of officials in other administrative agencies is not an unusual feature of presidentialism in many new democracies, especially in Africa. In South Africa the fragile detachment between politics and administration makes public office especially open to abuse.

What has come to be known as ‘state capture’ in South Africa saw the former president Jacob Zuma use his political discretion to bring friends and political allies into senior positions in government and in state-owned companies. Individually and collectively, they repurposed organisations, displacing them away from their official mandates to serve private interests and, more importantly, to channel huge resources for party-political purposes.

Indeed a judicial commission has examined the allegations of state capture, including corruption and fraud under former president Jacob Zuma, and recommended that there be changes to public sector practices and accountability, including to public sector procurement and the management of state owned enterprises. Many of the proposals focus on better policing corruption.

The Singaporean scholar Yuen Yuen Ang “unbundles” corruption into four types: petty theft, grand theft, speed money and access money. She shows that in China “access money” is the dominant type. This is a form of corruption that sees “rewards offered by elite capitalists to powerful officials in exchange for exclusive, lucrative privileges”. Whereas the other kinds of corruption have debilitating effects on government performance and development, Ms. Ang argues that in China, “access money” has been highly conducive to growth and the building of infrastructure. This explains the different economic trajectories of, say, China and India, for example, where ‘speed money’ – the payment for services to happen quicker – is pervasive in the latter. Like China, Ms. Ang proposes, South African corruption is dominated by “access money”. What we call “state capture” in South Africa comes very close to how Ms. Ang defines “access money”.

Why has state capture in South Africa not lead to growth and development seen in China?

An answer lies in the failure of the South African state after the end of apartheid properly to build merit protection systems. Even if infrastructure projects are awarded corruptly, China can still rely on a professional civil service to bring them to fruition. This is not the case in South Africa, where executive interreference in the machinery of government has destabilised many departments, agencies and state companies and burdened them with unsuitable, frequently incompetent civil servants and senior executives. Hence, corruptly awarded contracts are also poorly implemented or not implemented at all.

One of the insidious effects of state capture as a phenomenon is the way that it destroys public administrations from the inside. The repurposing of public institutions to serve private or party-political interests necessarily involves upsetting existing meritocratic practices or blocking such practices from taking root in the first place. A politicised civil service is the most severe constraint on growth and development in South Africa. It has transformed parochial disputes inside the ruling party into a national emergency. Reforming the architecture of government is the number one challenge for the country.

Between 5 and 7 July, the think tank on Government and Public Policy (GAPP) will host a major international conference on the Architecture of Government to bolster such reform efforts in South Africa. The intention is to consider the experiences of other countries in the global south and new south, also faced with formidable challenges of government, to consider options that could help South Africa complete its democratic revolution. You can register to attend to watch the event here.

Like this story? Sign up to Global Government Forum’s email news notifications to receive the latest updates in your inbox.

Senior Management the so called SMS has been pampered so much in South Africa. I was placed in Middle Management for years, no promotion Now I understand, the whole country, except for Western Cape is in tatters, this government must go now